Irish genealogy: missing records and amazing memories

In this article regional executive Kay Morgan looks at the challenge of researching Irish family history and explains why she finds it so rewarding.

Irish genealogy is a law unto itself, but it challenges you to think on your feet.

Irish genealogy is a law unto itself, but it challenges you to think on your feet.

One of the chief stumbling blocks for a researcher is that many records – particularly census returns – were destroyed in the civil war. And although full civil registration of all births, marriages and deaths began in 1864, non-registration was a major problem particularly in the period leading up to Irish Independence.

For most Irish people, baptism was what mattered, but again that causes a problem for researchers as indexes and baptismal records for the twentieth century are not easily available. Some of these records are coming online soon, but at the moment you often have to contact individual parish priests in order to get a transcript.

Anyone tracing Irish ancestry faces these problems, but there’s an additional obstacle for probate researchers, who not only track families backwards through time, but also forwards to find living beneficiaries.

Within the UK, there are several ways of searching the electoral register online to find someone’s current address. There’s nothing as straightforward as this for the Republic of Ireland, and although there are workarounds, often you have to go out and knock on doors.

Which is great, because there’s no-one more helpful than the Irish!

Townlands

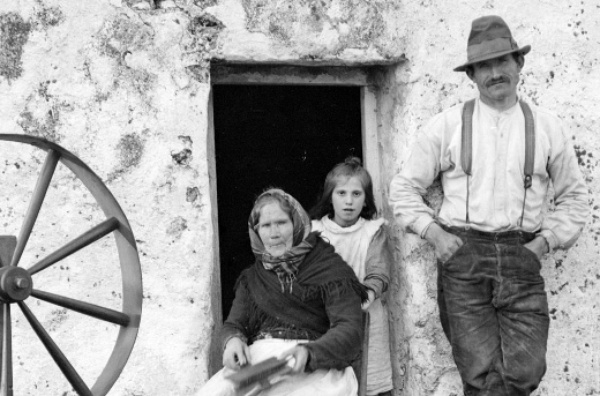

When looking for surviving beneficiaries, often the only address I have is the name of the townland where they may have once lived. Townlands are geographical divisions that date back to before the Norman conquest and survive only in Ireland.

They vary in size. In rural areas, a townland might be quite a large tract of land, with a sprinkling of widely scattered farms and cottages. Usually I have no idea which house contains the person I’m looking for, so I will knock on the first door I see and ask to be pointed to the most elderly person in the townland. Generally the oldest person can, fingers crossed, set me off in the right direction and sometimes they can even tell me everything I need to know.

No case illustrates this as beautifully as that of James O’Brien, who died intestate in Manchester with no apparent next of kin.

I traced his birth back to a townland in County Clare, where I interviewed his old school friend Michael Duffy, in the hope that he would perhaps give me some scraps of information about surviving family members. It was the day after Mr Duffy’s 100th birthday.

I have never met anyone like him. The only prompting I gave him was the name of the deceased.

A grand old gent

His memory of his childhood and young adulthood, and of the people I was trying to find out about, was simply unbelievable. He was able to recall all the O’Briens in chronological order, including the grandparents who’d been born in the 1860s. He even knew where the grandparents came from.

He told me that two of the deceased’s brothers became priests and went to Africa; one sister became a nun and another trained as a nurse in London, but died early of ‘blood cancer’.

At the end of the interview, I thanked him profusely, and teased him: “This isn’t good enough, Michael. You’ve killed them all off!”

Names, places and dates – everything checked out. Later, documented research confirmed he was correct in every aspect. The family had died out. This was one estate that belonged firmly in the hands of the Crown.

For obvious reasons, then, I am a firm believer in the value of communication. While I love the discipline of research, of carefully piecing the records together to find all the family relationships, it’s often talking to people that solves a case.

Though in some instances you have to keep ’em talking. I remember once knocking on a door, looking for a Patrick C Doyle. The elderly gentlemen who answered claimed to be Colin Doyle.

Of course, every genealogist knows that over generations a single family can spell their surname in a wild variety of ways. In Ireland, the problem is further complicated because people may swap between Gaelic and Anglicised versions of a surname and, to top things off, the forename on a birth certificate may not match the name an individual actually uses. For example, on paper a boy may share a forename with his father and grandfather, but never use the name in his life.

The date of birth Colin Doyle gave me matched the one I had for Patrick Doyle. I asked for his parents’ names. They matched the names I had. Everything matched, but: “No, no,” he wasn’t Patrick Doyle.

It took a full half hour’s conversation before he slapped his forehead and said “I’m an eejit!” All his life he’d been known as Colin, but he had been christened and registered Patrick Colin Doyle.

That was a case where persistence paid off.

(For reasons of confidentiality, names and other identifying features have been altered.)

2025 Anglia Research Services All Rights Reserved.

Anglia Research and Anglia Research Services are trading names of Anglia Research Services Limited, a company registered in England and Wales: no. 05405509

Marketing by Unity Online