How murder affects inheritance rules

Recently one of our case managers was searching through historic records when she stumbled upon a probate entry for Frederick Walter Stephen West, better known as the infamous serial killer Fred West who died in January 1995. In this article, legal researcher Rosie Kelly, fresh from success in her CILEx criminal law examinations, looks at the rules of inheritance when a murder has been committed and how these have evolved in recent years.

Frederick West of 25 Cromwell Street, Gloucester, notoriously murdered at least 12 young women between 1967 and 1987, most with the help of his wife Rosemary West. He buried several of the bodies in the garden of his property at Cromwell Street.

In 1995 West hanged himself in prison while awaiting trial. A year later Gloucester City Council purchased – and demolished – West’s house. The money from the sale of the property went to the Official Solicitor, who oversaw West’s estate for the benefit of his five youngest children.

The forfeiture rule

West’s victims were not people from whom he might inherit, and there are no legal provisions in the UK which would prevent a murderer from leaving money to his blameless offspring.

However, under the common law, in the UK there is a long established position known as the forfeiture rule by which a murderer cannot inherit from the deceased whom they have killed. This precludes an individual who has unlawfully killed or aided, abetted, counselled or procured the death of another person from benefiting in consequence of the killing.

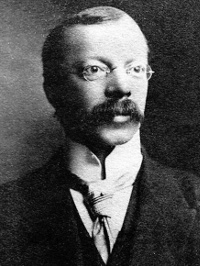

In the Estate of Crippen [1911] the judge, Sir Samuel Evans, explained that under the law:

no person can obtain, or enforce, any rights resulting to him from his own crime; neither can his representative, claiming under him, obtain or enforce any such rights. The human mind revolts at the very idea that any other doctrine could be possible in our system of jurisprudence.

A similar rule exists in the USA, where it is often referred to as the slayer rule. and it is easy to see the practical and moral reasons for the widespread existence of such a rule given that it removes any financial motivation for heirs or beneficiaries to murder their wealthy relatives.

Exceptions to the rule

Because the blanket application of the rule went against the public conscience in particular circumstances such as mercy killings and failed suicide pacts, the Forfeiture Act 1982 gave discretion to courts in England and Wales to allow some flexibility in applying the rule for cases of manslaughter where there are mitigating factors.

Section 2(1) states that the court must have “regard to the conduct of the offender and of the deceased and to such other circumstances as appear to the court to be material”, applying or modifying the rule as “the justice of the case requires”.

In Dunbar v. Plant [1998], the claimant Miss Plant had previously been found guilty under the Suicide Act of aiding and abetting suicide after a suicide pact with her partner Mr Dunbar left him dead while she survived. Mr Dunbar had taken out life insurance from which Miss Plant stood to benefit and the couple had jointly owned property. The Court of Appeal granted relief from the forfeiture rule because of the desperate circumstances that had led to the couple making the pact and the tragedy of the outcome.

Re K [1985] is another case typical of the circumstances under which the courts’ discretion under the 1982 Act tend to be invoked. Here a wife who had been convicted of manslaughter after pleading guilty to accidentally killing her violent and abusive husband was granted relief from the forfeiture rule and allowed the £1000 he had bequeathed to her by will.

A high bar to overcome

Nonetheless, a 2015 High Court decision in Henderson v. Wilcox & Ors [2015] illustrates how, unsurprisingly, the courts have been cautious in their willingness to exercise their discretion.

In this case, the claimant was a 63 year old man with learning difficulties who had previously been convicted under criminal law of the manslaughter of his elderly mother after satisfying the court that he had not intended to kill or seriously injure her.

The media had reported the case as a tragedy in which the man, who had been cared for by his mother his entire life, had found himself incapable of looking after her when the roles were reversed and she became dependent upon him. He brought a civil claim for the inheritance his mother had left him in her will – her entire estate with a value of around £150,000 – which would normally have been forfeited under the common law rule.

Despite the circumstances of the case and some apparent sympathy for the claimant, the judge did not modify the forfeiture rule as he was permitted under the 1982 Act but instead dismissed the claim (read the full judgment here).

Effects on the rules of intestacy: the ‘innocent grandchildren’

The most recent change to the law around murder and inheritance in England and Wales arose from the case of Re DWS (deceased) [2001]. A man had murdered his parents, both of whom died intestate. The Court of Appeal held that both the murderer and his child were excluded from inheriting, the former through the forfeiture rule and the latter through the rules of intestacy. This was because under section 47(1)(i) of the Administration of Estates Act 1925, the child could not inherit from his grandparents while his father was still alive.

The court thus applied section 47(2) of the 1925 Act, distributing the estate to the deceased’s sister as if the deceased had died without issue. This approach was widely criticised and was taken up by the Law Commission, who set out their recommendations for reform in their 2005 report, The Forfeiture Rule and the Law of Succession. This led to the Estates of Deceased Persons (Forfeiture Rule and Law of Succession) Act 2011 which remedied the anomaly.

Under the 2011 Act, if a person loses his or her right to inheritance under the forfeiture rule they are treated as having died immediately prior to the deceased for the purposes of inheritance. In this way, innocent grandchildren are still able to inherit.

2025 Anglia Research Services All Rights Reserved.

Anglia Research and Anglia Research Services are trading names of Anglia Research Services Limited, a company registered in England and Wales: no. 05405509

Marketing by Unity Online